How the DTC West Was Won

Capturing 10+ Years of eCommerce by: TJ Ferrara and Andy Nguyen

Sep 10, 2024

Intro

If you built an online brand and made it big in the 2010s, congrats on striking gold with impeccable timing.

And if you’re actively running a brand or just starting out, you might just be a digital miner.

If you’re currently in the field trying to find your fortune, we’re hoping this gives you direction on what’s happened and where to go next.

As eCommerce veterans and Californians, it’s interesting to see the parallels between the Gold Rush and the 2010s DTC Wave.

By comparing the early gold rush miners to the old guard of DTC brands like Glossier, HIMS, and Dollar Shave Club, we can understand how they built their empires, and what paths still exist for newer DTC brands to win.

So we’ll be covering how these brands built their empires during the DTC Gold Rush, why running a brand today is harder than ever, and how brand owners can win in the most competitive era.

The Thesis

The 2010s have defined the last 15 years of consumer shopping behavior.

From macro brews and shopping at outlet malls to craft beer, vegan mascara, and unconventional glasses all delivered to your door, these trends started here.

Out of thin air, brands like Dollar Shave Club and Warby Parker popped up and went toe-to-toe with the Gillettes and Luxxoticas of the world.

Why couldn’t the existing incumbents launch millennial focused or price friendly products like the brands above?

How did these unknown upstarts blitz out the incumbents as the world was coming out of the nastiest recessions we’ve ever seen?

While there was a big change in consumer behavior favoring small batch indie-styled brands, the rising tides that lifted everyone’s boat were:

The Economy (low interest rates + ZIRP)

The Tech (The launch & “Wild Wild West” of paid ads, big data, Device IDs, and Shopify)

The Inertia from Big Brands

The Hipsters (early adopters)

The brands that won in the 2010s took advantage of all these factors, and adapted with a fast changing market & consumer that moved their dollars + eyeballs from the mall to their phones.

The Economy

As the USA worked to recover from the Great Recession of 2008, we saw historically low interest rates through Quantitative Easing (QE) to encourage lending and (indirectly) more aggressive investments.

This policy made it easier for brands and businesses to borrow money for growth, significantly impacting debt and venture financing for DTC brands and tech companies.

Companies like Klaviyo, Braze, and Shopify benefitted from this and were able to attain the fundraising necessary to build the tech infrastructure that powers today’s online retail software stack.

This environment also made it easier to justify spending resources on new advertising channels like Google Ads and Facebook, and coincided with the materialization and popularity of mobile apps, online storefronts, and other digitized businesses.

Lower rates allowed DTC brands to serve smaller pockets and niches of the market that weren’t being properly addressed before.

While monetary policies like ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) helped to stabilize the economy, it also boosted the ability for new brands to explore the DTC business model and serve smaller, niche pockets of the consumer market that were not adequately recognized before.

With cheaper money, it was a much friendlier environment to keep swinging until you found that niche that leads to product market fit (especially in the midst of changing consumer tastes).

And while a finance-friendly environment was crucial, the ability to reach untapped parts of the market and build a brand catering to your niche was only unlocked by the massive leap in consumer technology via iPhones and ads targeting.

With Google and Facebook collecting mass amounts of data to target users by their phones, brands could target customers on nearly a 1-to-1 level.

You could truly target the exact type of people you were looking to reach, avoiding marketing waste and advertising with extreme precision.

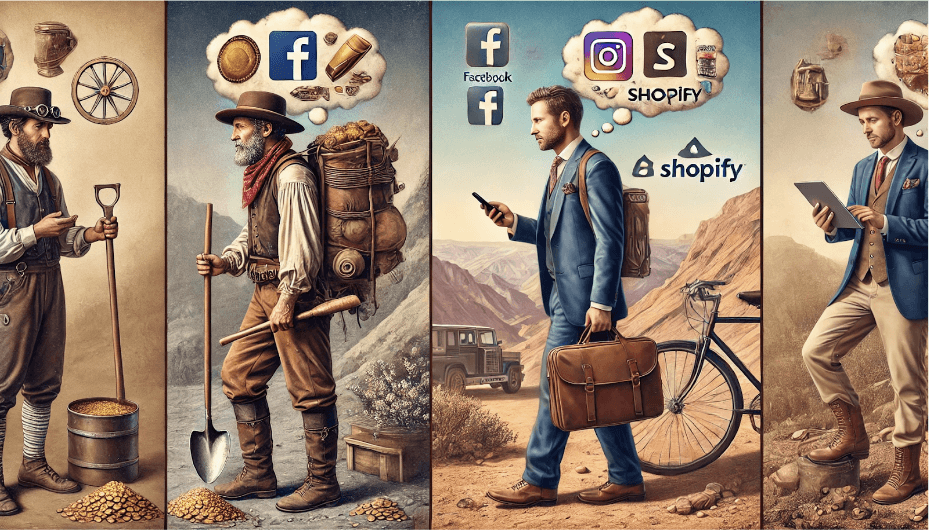

If you were lucky enough to be one of the first brands to advertise through Facebook, Instagram, and Google, you had first dibs on all the caves and land settlements filled with gold.

In the 2010s, these ads were novel. You didn’t have to deal with the saturation of paid advertising on Instagram and Facebook that shoppers are facing now.

Additionally, the economic conditions of the 2010s allowed brands to get extra resources from these ad platforms. Not only did Meta and Google provide shovels for brands to dig for gold, they even provided accelerator programs like FBStart and FBCommerce to seed their ad network by business verticals. DTC brands and tech companies like Instacart, Postmates, and Uber were given extra resources, account managers, and workshops to scale on these advertising channels.

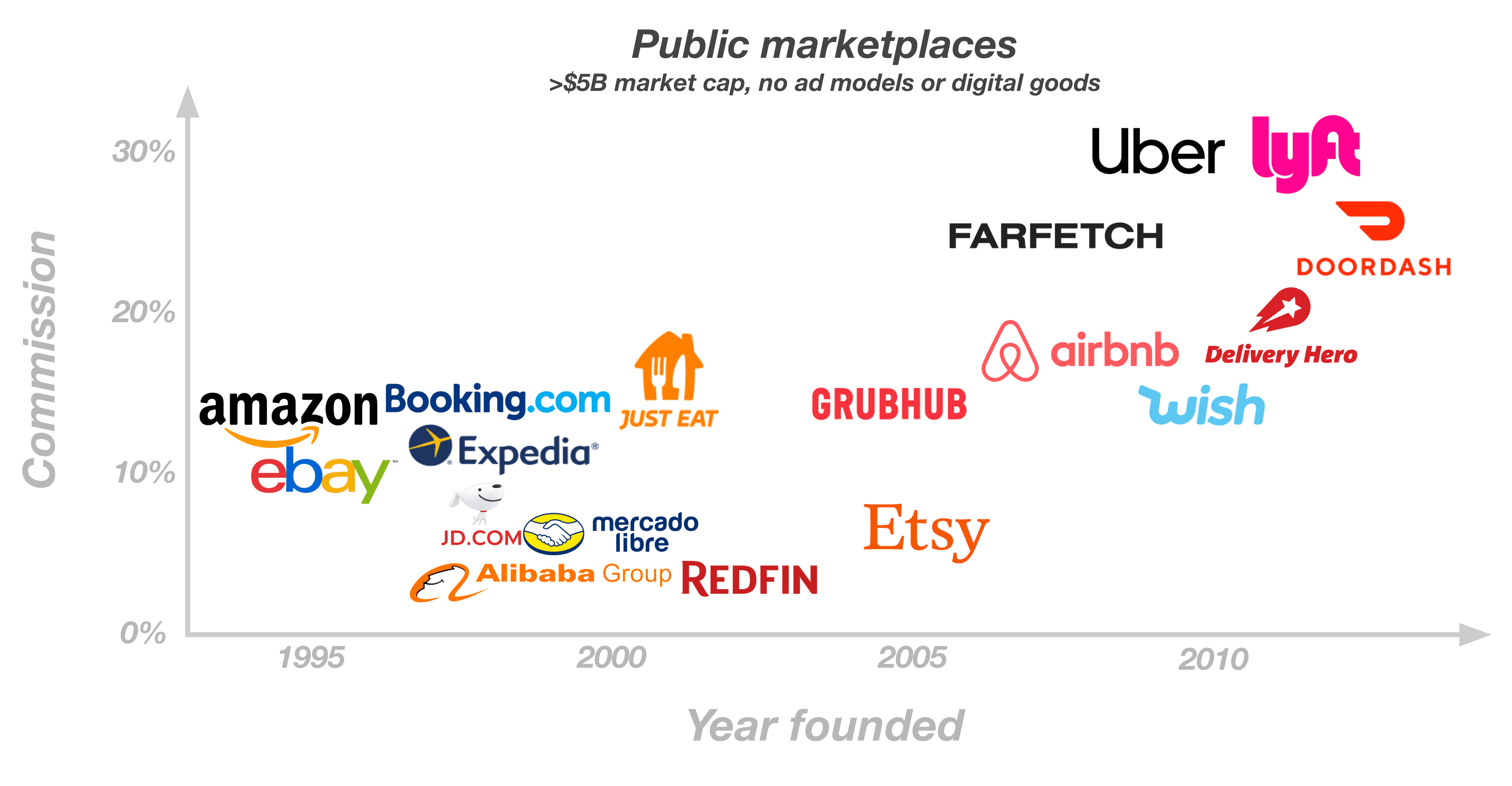

The 2010s also set the stage for some of the biggest consumer commerce companies to emerge since eBay:

Uber, $150 billion market cap

Airbnb, $73 billion market cap

DoorDash, $52 billion market cap

Instacart, $9 billion market cap

These high tech commerce marketplaces had extremely thin operating margins and likely could only be financed during the 2010s macroeconomic environment.

And just like them, if you were in position to take advantage of this window, you hit it big.

Like the miners who arrived in California in the late 1848 to early 1849, these folks had the best chance of finding rich deposits of gold and exiting at the top.

They could strike it rich and extract gold with a simple pan, sluice, or cheeky Facebook Ad. You didn’t have to go deep into the mines, you likely exited at the top by getting acquired or through a SPAC.

You didn’t have to compete in a post iOS 14 world, a higher interest rate environment, or against the saturation and hyper-competitiveness of eCommerce today.

The Tech

You ever get an ad on your phone and question if someone was listening to every word you say?

What actually was happening was this– advertisers were building a scrapbook of every person’s online behavior.

Our phones and ad networks constantly track us. They collect data, train, and evolve. From what you like, post, and purchase (online or inside a store), your online browsing behavior to your credit card transactions were all linked and recorded at an individual level through “Identifier for Advertisers”, or IDFAs.

First released in 2012, an IDFA is a unique identifier Apple assigned to each iPhone (the Android equivalent being GAID, or Google Advertising ID) to help advertisers track users’ journeys, interactions, and behaviors. This device ID allowed advertisers to target users on an individual level through precise, customized advertising, creating a paradigm shift in performance marketing.

Rather than spending on broad marketing campaigns like billboards or television ads, brands could be ruthlessly efficient with advertising spend. If your ads were hitting the right people at the right time, you were probably reporting a 20x return on ad spend on Facebook. For Google, lower CPCs and competition (compared to now) on strategic keywords or search phrases were pretty much greenfield and ready for folks who were smart and early enough to buy low.

The amount of information Facebook and Google collected on users, the speed at which you could experiment with audiences/ad creative, and the unparalleled ability to target the right people with the right ad created a perfect storm for brands to iterate their way to product market fit.

Device IDs were so critical to the success of DTC brands that once Apple restricted IDFAs from Google/Facebook (in an attempt to center Apple Search Ads), every advertiser scrambled to unscrew their drop in ROAS. Earning reports felt the impact of IDFA removal and brands gasped at the decline in their ad spend returns.

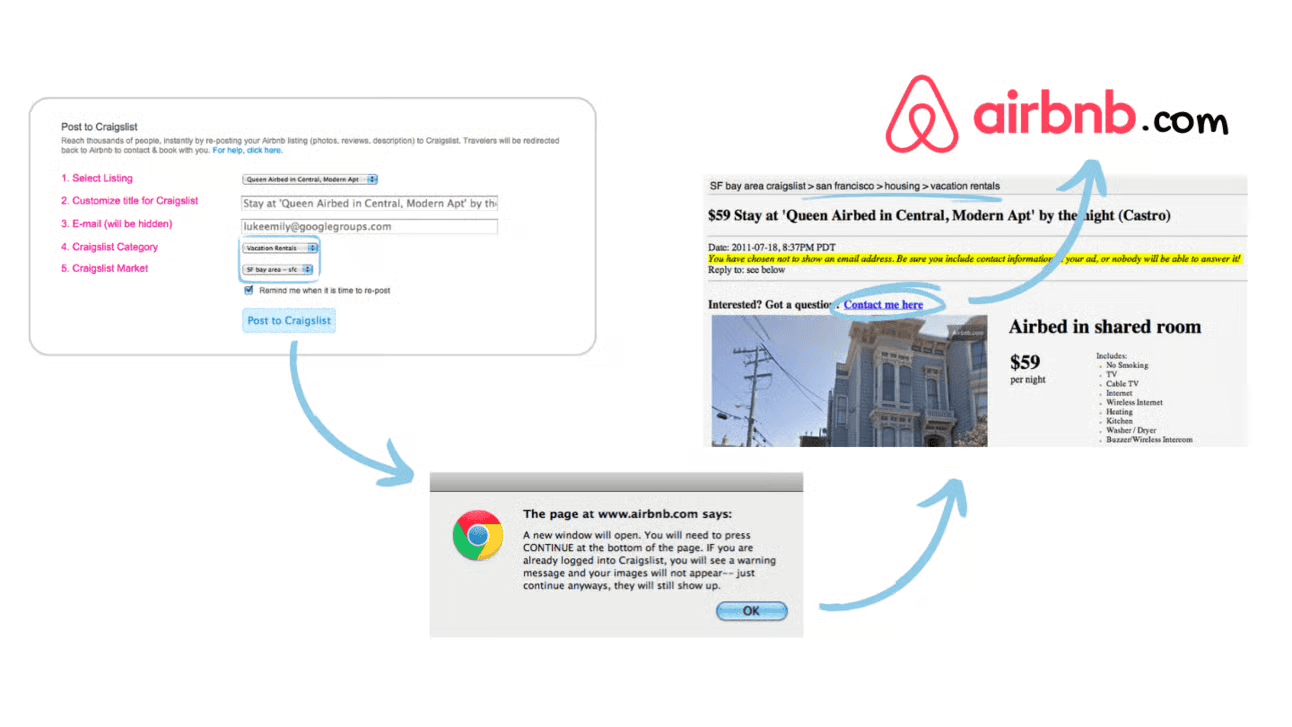

While you might hear some revisionist takes on the blitz-scaling brands did through paid ads in the 2010s, the term growth hacker started around this decade. Whether it was hacking the Craigslist’s API to spam AirBnb listings, leveraging device IDs for better ads, or using LTV models to maximize bidding strategies, the brands that won in the 2010s did so by leveraging consumer data and blitzscaling on ads. Inversely, a lot of incumbents who weren’t fast enough to adapt ceded market share (Abercrombie, Macy’s) or died (Sears, KMart, Sports Authority).

In conjunction with consumer data and advertising platforms, the 2010s gave birth to the infrastructure that powers eCommerce today. Online commerce platforms like Shopify made it extremely easy and accessible for founders to start building an online brand. At the same time, platforms like Braze and Klaviyo encouraged and improved email and SMS marketing that spurred eyeballs to online stores.

Between email, push notifications, and SMS marketing, eCom advertising, and online store platforms like Shopify, you could have a storefront and marketing department within a week.

It became lightning fast to get product validation and feedback. And this became a marketing stack brand owners used to scale. Factor in a black-swan event like Covid where you had to buy everything online, you start to understand how important these tools were for online commerce.

As a reference for impact, Shopify is now worth over $95 billion and is 34% more valuable than Target in market cap.

While consumer spend shifted to digital from physical, Web 2.0 was in full swing.

Affordable iPhones and Androids, faster internet speeds, constant content generation, and the emergence of social media ‘influencers’ sparked the robust growth of consumer attention and spending online. Ad retargeting, push notifications, customer data platforms (CDPs), and attribution providers (MMPs) were ushered in the 2010s and allowed brands to outpace the incumbents that were too slow to retool their marketing tools for these new channels. The DTC brands that took early charge of this momentum and evolved their strategies to meet this new online consumer culture leaped ahead of the competition.

For the brands that were slower to jump on this, we don’t think it was purely a skill issue. In order to win on ads you still needed funds to advertise or budget to buy the tools for these eCommerce channels. The more money you spent on your ads, the more frequently they showed; in theory this should drown out smaller-spending brands. With funding and budgets continuing to hold importance, why is it that large department stores and big-box retailers struggled against the rise of new online DTC brands?

Is it possible large retailers felt too safe and familiar with the crafting of traditional television commercials or magazine ads, and failed to see the rise in popularity of influential online channels like YouTube/Instagram?

Is it also possible that marketing teams from traditional brands or retailers simply couldn’t adjust to the changing consumer market fast enough? Or did they simply just write off the importance of a new advertising channel?

The emergence of social media influencers and the popularity of social platforms like Instagram and YouTube generated a massive push for brands to partner with influencers to distribute or promote products.

The concept that any individual could grow their following and become an influencer was revolutionary to the times.

(If you're unfamiliar with the person on the right, they're literally an AI influencer that's done brand deals with Samsung & Calvin Klein. If you're unfamiliar with the person on the left, just know they were decent at basketball.)

You no longer had to be Michael Jordan or Martha Stewart for brands to hire you for product promotion.

Average individuals putting out popular lifestyle content and accumulating thousands of followers became attractive for brands to partner with as they exemplified a ‘relatable’ feel and connection with their audience like a more precise and interactive billboard ad.

The dawn of influencers (and eventually affiliate marketing) was started here and is now a pillar for DTC brand growth.

The 2010s also saw big improvements in supply chains and third-party logistics, which fostered the growth and popularity of drop-shipping. Businesses could now sell products without holding any actual inventory. Suppliers like Alibaba made it cost-effective and attractive for businesses to choose to drop-ship and focus their efforts on website presence, marketing, or other retail activities instead of product inventory.

You no longer needed to open a production center in America to sell pants. Allbirds, founded in 2014, initially made their shoes in China. Warby Parker, founded in 2010, also sourced their frames in China. Casper, Fashion Nova, MVMT Watches, and Brooklinen all had ties in sourcing initially from Chinese suppliers.

As a result of new technological advances that emerged in the 2010s, the opportunities to build a brand magnified and facilitated a new era of global commerce–an era in which we are still living and selling. Consumer data-driven advertising, niche markets, social media, online storefronts, influencers, and inventory outsourcing have all played a significant role in the rise and adoption of mobile commerce.

If the economic conditions were the rising tide for everyone’s boat and kicked off the gold rush, mobile phones and marketing tech were the hydraulic mining techniques that allowed people to extract as much gold from wherever they were mining (which happened to be in our mobile phones).

The Inertia

If you’re a big brand, you don’t have to move as fast as the smaller ones. But if you’re a small brand starting out– hustle, momentum, and speed kills.

New tech helps as well. Smaller brands could and were competing with traditional retailers. You could rapidly iterate, test, and experiment your way and lock up an entire patch of gold by building for a specific consumer interest or product.

Big retailers for whatever reason couldn’t adapt. Regardless of existing marketing teams, relationships with suppliers, MBAs, or financial leverage, the Macy’s, JCPenney, Targets of the world were all examples of retailers that were in much stronger positions to start and build any of the DTC brands we’ve listed (Everlane, Harry’s, etc.).

We don’t have a good answer for why this was the case.

Was it the finance team not wanting to test or budget for a new advertising channel? Was it the comfort of going with a tried-and-true method post Great Recession, or that the cash cow revenue streams were too good to pass up?

However, even with agility and hustle, there was a problem all these new brands faced, distribution.

What we saw in the craft beer industry with Rogue Ale, Allagash or Sierra Nevada brewing, was the perfect precursor for consumer retail.

While we saw popular microbrews find distribution into bars across cities and college towns to compete with macro brew companies, DTC brands still needed to get that next tranche of eyeballs and traffic that couldn’t just come purely from online channels.

So digitally-native brands got their next growth wave by either going digital to physical (e.g. Warby Parker, Everlane, Allbirds), or exiting to brick-and-mortar businesses like:

Dollar Shave Club to Unilever for $1 billion

Bonobos to Walmart for $310 million

Chewy to PetSmart for $3.35 billion

Casper to PE Firm for $286 million

Native Deodorant to P&G for $100 million

MVMT Watches to The Movado Group for $100 million

For both big and small brands either looking to grow their consumer base or maintain relevancy, M&A played a big role for everyone to get to the next stage, or to play catch-up with changing customer segments.

The Hipsters

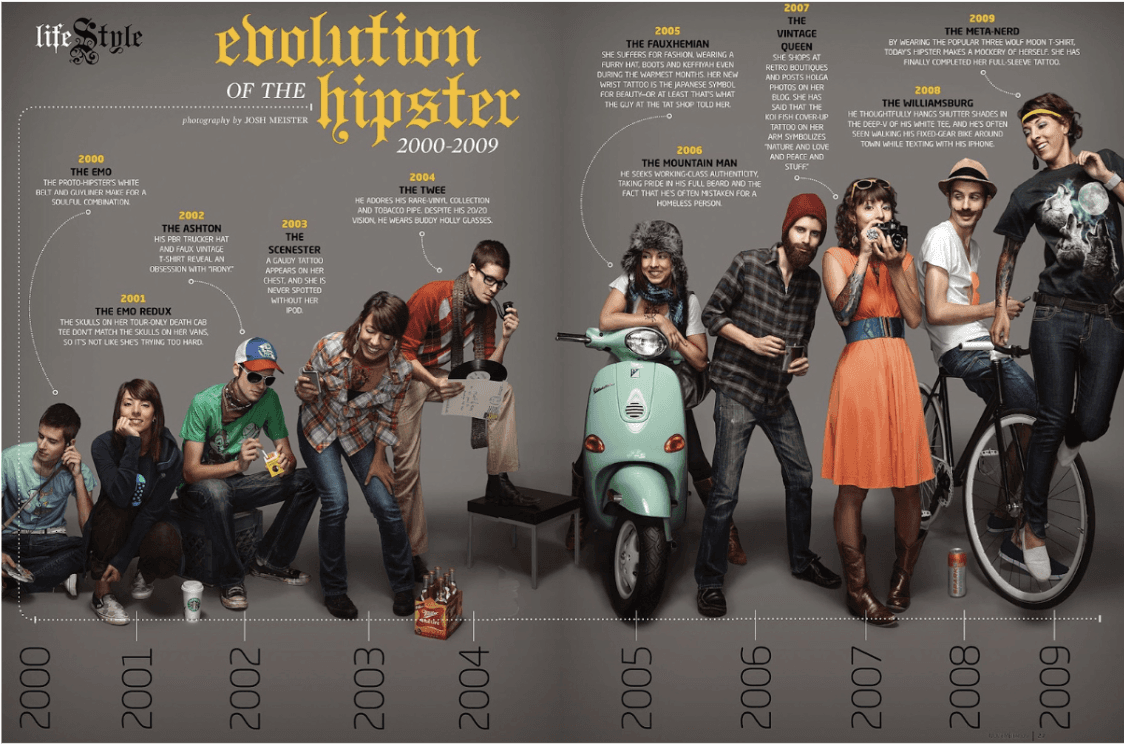

As we’ve covered the tech advances that paved the way for DTC brands to succeed, it’s equally important to highlight consumer identity and demand in the 2010s.

A shift in economic and cultural factors–a consequence of the War in Iraq, the Global Recession, and the Bush Administration–reshaped the millennial consumers’ buying behavior.

What followed was a purge of the mainstream in favor of social reform that adopted new trends and celebrated originality.

Eco-friendly, sustainable, craft or micro-batch goods were not just adjectives applied to goods but an identity withheld and prized by a mass market of consumers considered ‘Hipsters.’ People sought goods and services that deviated from the conventional–and built their identities around doing so.

A subculture of being progressive and quirky was on the rise. To counter the rising cost of gasoline, some folks started riding Fixie bikes. Mainstream news channels like CNN and Fox lost cultural relevance to mediums like Vice. From fashion to razor blades, it was ‘cooler’ to stand out from the crowd, and brands that catered to this became increasingly popular with the millennial consumer.

With social platforms like Facebook and Instagram, the consumer not only had exposure to emerging trends but the ability to find and connect with other groups of individuals that shared the same ideologies and interests.

These platforms fostered connection and demographic placement with ‘likes,’ ‘follows,’ and hashtags. DTC brands thrived off this. As cheesy and corny as it sounds, these folks were the early adopters that smart brands worked with to build, scale, and co-develop their products with.

It was the era of online presence and, thus, the online consumer. Traffic to malls began to dwindle; Shopping at a mall became almost ‘uncool.’ Brands with a story and crafty online presence were attractive to this consumer group. Relatable influencers could begin to sway trends or push products to mass popularity. Shopping was almost a subconscious transaction with digital accessibility and purchasing ease of subscription goods.

Consumers began to associate their identity with brands they felt ‘listened’ to their needs, paving the way for businesses like Warby Parker, HIMS, Everlane, and Dollar Shave Club to offer a personal story and solution for the customer. The brands that succeeded were those that listened and evolved with their customers.

Reflecting on an era of online shopping and digital popularity, it’s interesting to see the behaviors and habits of Gen Z consumers today. Nostalgia and generational changes seem to be pushing this generation away from existing online to living in real-time. Gen Z consumers appear to want this experience again, and we may eventually see malls and in-store shopping come back in vogue.

What will the future look like for eCommerce?

With a changing consumer base, online commerce must evolve as we shift from catering to Millennials to Gen Z buyers. Some experts think we're experiencing an oversaturated market, with brands having a hard time spotting who the next early adopters are to build for, and a plethora of marketing channels to sift through.

Can you spot who’s a hipster now and who’s not?

Can you build with early adopters or a community if anyone, anywhere can jump from one community to the next like digital chameleons?

The internet moves too fast. The speed at which content, culture, and trends are consumed/shared is instantaneous. There’s too much noise and turnover.

For a brand to find its initial niche customer group and to maintain relevancy is much harder today than it was in the 2010s.

How much should brands lean on influencer marketing? Are customers from these spokespeople actually scalable and retentive for your business? Online commerce success in China is relatively dependent on influencers, especially for livestream shopping which absorbs a significant amount of consumer attention and sets the pace for brand distribution.

For the Western World, we're personally skeptical as democratizing QVC hasn’t picked up as heavily for a multitude of reasons.

As the creator economy grows larger and larger, so do new pockets of consumers that are reachable through a wider variety of media and product consumption platforms. Brands can reach new customers not just through DTC methods but also through affiliate marketing, Meta, Amazon creators, TikTok creators, YouTubers, and so on. It’s tough for a brand to keep up and know where to spend your time.

The jury’s still out on the creator economy, but between Mr. Beast selling chocolate bars and burgers, or Logan Paul & KSI selling non alcoholic Four Lokos, there’s some interesting stuff here likely worth paying attention to.

Building Relationships

In sum, changing consumer interests, a new groundbreaking way to reach consumers that big retailers weren’t using, and favorable economic conditions allowed the big DTC brands to stake the claims that they did.

If you were in position to build a brand at this time, you likely had a strong chance to succeed.

You probably were all in on growing at all costs and maximizing all the tailwinds you had at the time, instead of worrying about your contribution margins or having all your cash flow tied up in inventory.

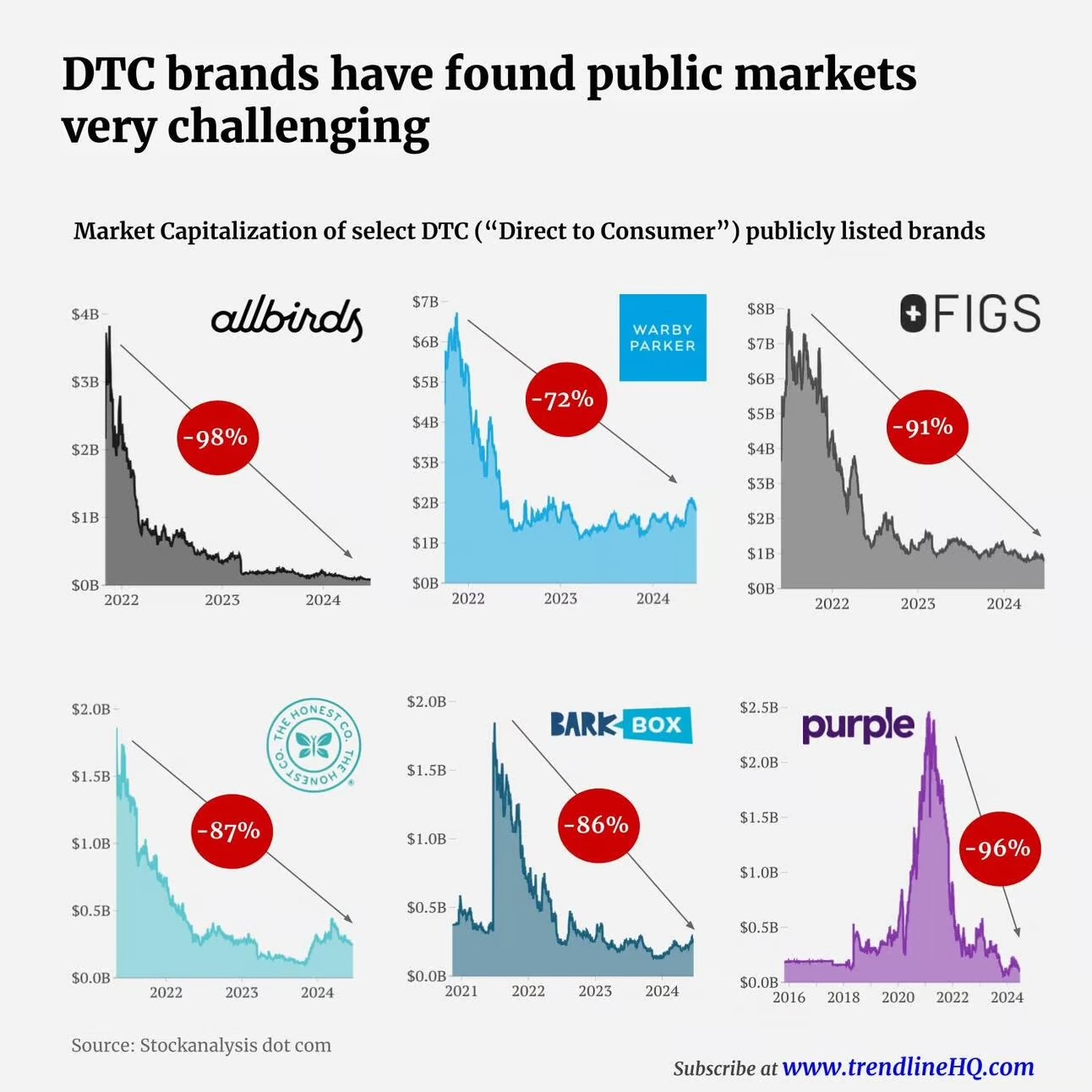

Those favorable conditions brands sailed on aren’t there anymore. There aren’t as many paths to the promised land.

Ask TJ who’s seen it all building and growing his DTC Collagen Brand, BUBS Naturals.

You are likely not alone if you feel like the gold mines are tapped out. The plight of the Gold Rush miner who arrived in California a day too late is similar to the circumstances of post-2020s DTC brands and upstarts.

Missing the top of the DTC wave and its coinciding technological advances was like showing up late to gold mine with a hammer and pick while others were already on to excavators.

So, how can new brands compete in today’s market?

While it’s never been easier to start a business, it’s never been more challenging to build something with enduring value.

The favorable conditions and opportunities from the 2010s simply don’t exist anymore, with paths to rapid success being few and far between.

Ask brands if they are still seeing the same ROAS (Return On Ad Spend) as they did years ago. Or, what revenue do you need to get a 3x exit on your business today versus 2018? Ask owners about increases in 3PL, shipping costs, or competitors constantly popping up in their space.

It’s no surprise conglomerates or holding companies have frequently picked up small brands that could not exit in time or are simply stagnant.

In an oversaturated market and a world with too much noise, you need to stand out and provide lasting, altruistic value. Build a brand on community and relationships instead of ads and new acquisitions. Mean something to your community.

We encourage new brands to create stories with the folks they’re building for and to collaborate with other operators as well. In today’s online spaces, there is too much noise, too much turnover, and a lack of real, meaningful connection or thoughts.

Instead of blanket ad campaigns, share something useful to your audience. Bring the human feel to the digital transaction. It’s literally never been easier to produce or source content, especially as AI makes content production instantaneous.

Small eCom brands can grow and win by keeping things personal and relatable to the consumer.

To help brands do this, TJ and I have been building scaffold.works, an AI email marketing tool that automates and personalizes emails to sell more and churn less.

We’re giving brands the same data-powered marketing engines that the Ubers, AirBnBs, and other top commerce companies used to scale their marketing channels.

If this helped catch you up on 10+ years of eCommerce, we’re glad for it.

For any questions, you can reach us at [email protected] or [email protected]. In our next article, we’ll expand on the challenges brands are dealing with in today’s economy and consumer market.

Best,

TJ & Andy